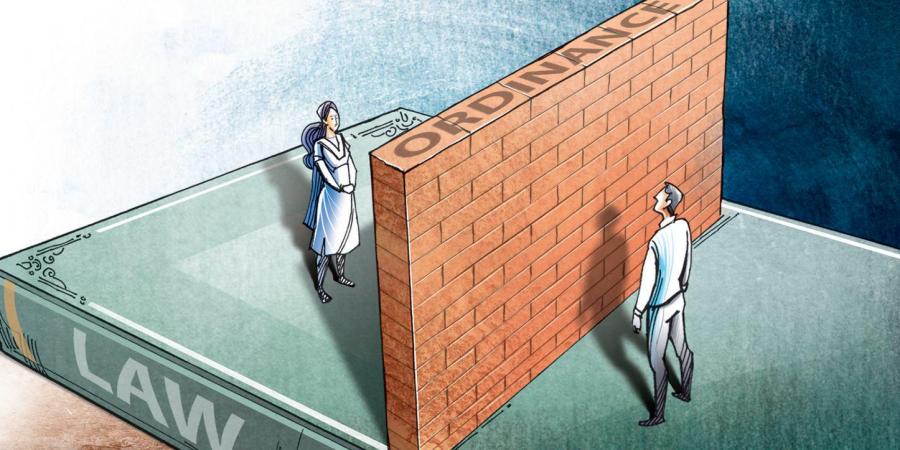

The Ordinance also goes against the right to privacy. The state has no role to play in the personal choice of individuals in consummating a union and embracing their partner’s religion

When laws are motivated by communally divisive agendas, they breed suspicion within communities, resulting in a sense of alienation. That in turn negatively impacts societal peace and harmony. Occasionally, it leads to sporadic violence. When such laws attempt to interfere with personal relationships or emotive issues of choice, which are at the heart of individual freedoms, the outcomes are even more disturbing. That explains why matters relating to marriage, divorce, succession and inheritance polarise dialogues and attitudes.

Such agendas germinate a majoritarian culture pitting “us” against “them” and give birth to electoral majorities. The road to power then becomes a relatively easy enterprise. The rise of right-wing assertions, a global phenomenon, is based on such engineered societal divides. The Uttar Pradesh government’s recent promulgation of the UP Prohibition of Unlawful Conversion of Religion Ordinance, 2020, relating to “Love Jihad” is yet another attempt, in a string of communally charged initiatives, aimed at reaping electoral dividends.

Love jihad is a concept the contours of which are blurred. However, in simple terms, all that it means is that if a Muslim boy, in love with a non-Muslim girl chooses to marry her and she embraces Islam, such a union will be looked upon with suspicion by the law and is liable to be declared void. This strikes at the root of individual liberty since such a union cannot be held to be legally suspect. It strikes at the core of the ‘right to privacy’, which is protected constitutionally.

The Ordinance also targets mass conversions, which have taken place in the past. These include conversions to Christianity in the 1930s, to Buddhism by Dalits in the 1950s and Mizo Christians to the Jewish faith in the 2000s. Those seeking to convert allure marginalised castes and tribes with hope, dignity and material enticement. Dr Ambedkar, disenchanted with the caste structure of Hinduism, converted to Buddhism.

The reasons for such mass conversions are complex and need to be addressed separately. Under the proposed law, those guilty of mass conversions are liable to face a jail term extending up to 10 years and a minimum fine of Rs 50,000. While it is justifiable to prevent conversion based on force, coercion, undue influence, misrepresentation and allurements, it is difficult to prove these elements if a Muslim boy and a non-Muslim girl or vice-versa exercise their free will to marry for reasons that are entirely personal. The reason why non-Muslims convert to Islam is because the children born in wedlock would otherwise be excluded from inheritance under Muslim law.

Absent this conversion, the union of a Muslim with a non-Muslim or vice-versa will be a difficult proposition. That is why the intent of the proposed law is suspect as it seeks to target conversion and not marriage. The Ordinance provides that in an interfaith marriage, if one of the partners wishes to embrace another religion, that person will have to inform the District Magistrate or the Additional District Magistrate in writing at least two months in advance. A format of the application seeking permission for conversion will be provided by the government.

Under the proposed law, it would be the responsibility of the person embracing another religion to prove that such person was not converted forcibly or through fraudulent means. Those who abet, convince or conspire are also liable to be prosecuted. Any such violation of the law would entail a jail term of six months to three years and a minimum fine of Rs 10,000.

Marriage between two people is personal to them. It allows either of them to opt out of the marriage. In addition, the person victimised is free to allege use of force, coercion, fraud, undue influence or misrepresentation against the other. In the absence of any of these, it is unthinkable that the law mandates a person who voluntarily embraces another religion to seek permission to prove that the decision was not actuated by any of those elements. Reversal of the burden of proof in matters of personal choices of a life partner may be legally unsustainable.

The obligation to seek permission for conversion two months in advance is fundamentally arbitrary and a violation of the ‘right to privacy’. The state has no role to play in the personal choice of individuals in consummating a union and embracing the religion of the partner. The state can certainly regulate acts of forced conversion but the starting point of such regulation has to be a complaint made by the individual who opts to convert. In most of these cases, it is the parents who complain that their daughter has been fraudulently enticed into a relationship and is a victim of forced conversion.

The Ordinance allows members of the family of those who convert or any relative to lodge an FIR. This makes the Ordinance an instrument of harassment in situations where interfaith marriages are voluntary.

We have seen this being played out in Hadiya’s case in Kerala. The couple went through trauma when Hadiya’s husband and some organisations were targeted for allegedly having induced her to convert to Islam. This was despite the fact that she constantly denied the allegations, asserting that she had embraced Islam voluntarily and much before she had met her husband.

The drama was then played out in court after the Kerala High Court held the marriage to be void on grounds that there was no reasonable explanation given by Hadiya for her marriage to a Muslim without the consent of her parents. Finally, while appearing personally in the Supreme Court, she unequivocally stated that she had married her husband of her own free will and converted to another religion much before her marriage. The National Investigation Agency (NIA) was asked to investigate the circumstances in which Hadiya had married and converted.

The NIA decided to widen its investigations. From a list of 89 such marriages, it investigated 11 cases and in the absence of prosecutable evidence, all such matters resulted in closure. The bottom line is that the Ordinance serves a political purpose. It is yet another way to polarise our polity. The issue is emotive and seeks to divide communities. The constitutionality of such a legislation when challenged should be decided with utmost speed. The court, hopefully, will find such laws to be antithetical to the constitutional ethos and our civilisational values. Any attempt to delay adjudication would only be playing into the hands of those intending to divide and not unite India.